Under Ceausescu

Ewing Toil

By Vivid writer: Christopher Lawson

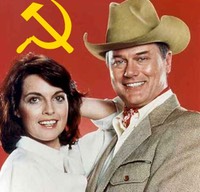

The apparatchik who permitted Dallas to be shown in Romania had committed a colossal blunder. Far from providing a warning against the evils of capitalism, viewers in this part of the Eastern bloc wanted to have it all, in thick slices

Posted: 18/05/2008

"Why don't you come and stay at my place for a week or so? My wife's a German-speaker. She'd be pleased to meet you. You can give our daughter some practice with her English. And Dallas is on tonight. We'll be having the gang over."

"But you know foreigners aren't allowed to stay at Romanians' houses overnight," I intoned virtuously, although the wine we had shared in the restaurant car had emboldened me. Not that I was especially worried. This law was almost impossible to police.

"It's the best possible entertainment," they chorused, "powerful men, beautiful women in fabulous clothes, and unimaginable barrel-loads of money."

"Don't insult me - come along," ordered my new host, an economist, in the schoolboy French we'd been conversing in for the past few hours. We hefted our bags out of the train and took the trolleybus into the centre of Sibiu. It was the spring of 1979.

Almost as soon as we had settled ourselves in his apartment, his wife arrived, weeping with laughter. Between giggles, wiping her eyes with a handkerchief, and without being introduced to me at all, Andrea told her story.

"So they closed all the factories, shut down the schools, issued Romanian flags and lined the people up along the route," she explained. "But it was the wrong route! The official motorcade with Ceausescu in the lead car passed through empty streets. So there'll be no people waving flags on tonight's news, no clapping children. God knows how they'll fill the missing minutes."

Still delighted by this small victory over communist organisation, a huge cock-up by the party, the couple began busying themselves for the major event of the evening. They were one of six couples that took turns to prepare food and wine for the weekly episode of the Ewing family saga.

It was pure escapism, of course. But all these thirty-something Romanians identified themselves totally with JR, Bobby, Sue Ellen and their extended families. "It's the best possible entertainment," they chorused, "powerful men, beautiful women in fabulous clothes, and unimaginable barrel-loads of money." And behind the power struggles and the tantrums, as countless social anthropologists have since testified, lay of course the future, and the whole question of who would inherit the ranch.

The apparatchik who permitted Dallas to be shown in Romania had committed a colossal blunder. Far from providing a warning against the evils of capitalism, viewers in this part of the Eastern bloc wanted to have it all, in thick slices.

With my daughter, I visited the family often after that first meeting. On the last occasion I stayed, in the 1990s, the couple and their friends were running several successful businesses, and coming into their apartments with great wedges of cash.

It was munca patriotica (eng: patriotic work) and munca practica (eng: practical work), the bane of foreign lecturers' lives, which first kindled my twin passions for travelling on Romania's trains and visiting graveyards.

For munca patriotica students picked grapes, harvested maize or sorted potatoes according to the rural area where they were sent. With two weeks off classes, loosely supervised by teachers, they played games when not working and slept in beds in collective farm buildings. I can't tell you about the food because most skipped the meals provided. Their working days weren't too arduous and many had already been harvesting in their schooldays.

The fortnight away from classes played havoc with the academic rhythm of the semester, laboriously established in the first two weeks. Within a matter of another month and a half, it was time for munca practica. Students were attached to other departments, primarily in economics, and translated screeds of texts into a kind of English. If the value of the translations was questionable, it did teach students to touch-type.

And so, with time on my hands, at the recommendation of a Romanian colleague, I took a Round Romania ticket. The train passed Vatra Dornei, in the mountains, where the Ministry of Historic Buildings is now restoring the pre-war casino. I spent a couple of days in Cluj, and remember a graveyard where one gravestone boasted both a cross and a hammer and sickle: the late lamented obviously believed in double insurance. In Timisoara I hurriedly got off a trolleybus, anxious to preserve my dignity as a British lecturer, when I found that my two companions were not buying a tickets "as a protest against the communist system". In a Saxon church in Sighisoara, I watched an elderly woman tend an immaculate grave and plant fresh primroses. "Weit von seinem Land ruhet ...." read the inscription, for a soldier lost on the Russian front. I found the scene unbearably moving.

I was most impressed by the Romanian custom of burying allies and enemies side by side: Here lies a Romanian hero. Here lies a Hungarian hero. Here lies a Russian hero. Here lies a German hero. Surely there is hope for a country, which practices reconciliation as generously as this?